Today, I did my first sermon, as a guest speaker at Northlake Unitarian Universalist Church in Kirkland. The month’s theme was Stories, and my sermon was entitled “Stories Inspire, Educate, and Change Hearts and Minds.”

Here are the readings, and the sermon:

Centering Words

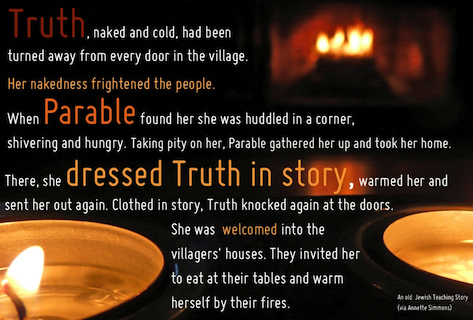

This is a Yiddish teaching story, told since the 11th century in various forms

“TRUTH, naked and alone, walked into a village. The local inhabitants immediately started cursing at her and chased her away. TRUTH walked along the road to the next town, and they spit at her and spewed epithets until they drove her out of town. She continued walking down the road, hoping to find someone who was happy to see her, someone who would embrace TRUTH with open arms.

So she walked into the third town in the middle of the night, hoping that the townsfolk would be happy to see TRUTH in dawn’s light. But as soon as the townsfolk saw her, they started throwing garbage at her. TRUTH ran off, into the woods, crying.

Later, she heard laughter, singing and applause. From the woods, she could see the people welcoming a creature named STORY as she entered town. They brought out fresh meats and soups and pies and pastries and offered them all to STORY, who reveled in their love and appreciation.

Come twilight, STORY found TRUTH huddled in a corner, shivering and hungry. Taking pity on her, STORY gathered her up and took her home, saying ‘I am sorry they rejected you. No one wants to look at the naked TRUTH.’

So STORY lent TRUTH some of her beautiful garments to wear and they walked into town together. The townspeople greeted them both with warmth and love and appreciation. They welcomed TRUTH into their houses, and invited her to eat at their tables and warm herself by their fires for TRUTH wrapped in STORY’s clothing is a beautiful thing and very easy to embrace.

Ever since then, TRUTH has travelled with STORY, and when they arrive together, they’re both accepted and loved.

That’s the way it was, that’s the way it is, and that’s the way it will always be.”

———

Reading – Merna Hecht, local storyteller

We really have two kinds of languages. One is Logos, rationality, which is essential to us. We have to be informed, we have to be conscious, and we have to be rational in order to discern our world. But there is also the language of Mythos – imagination and spirit. We have to have both kinds of experiences to be whole human beings.

The rational mind keeps things objective, outside of us. Story brings what’s external to us inside and makes it subjective; and at the same time it objectifies what’s inside of us, takes it outside.

Story prepares us. Life is not happy. It’s full of loss and gain, of leaving and returning, and Story is also full of that. It makes the human condition meaningful and bearable, and it puts us in community. It gives context to our lives, and yet it also allows for wonder in the outside world. Story can help us develop resonant relationships with the world.

Those human moments where you can feel the suffering of other people – where you can put on the shoes of one man or one woman or one child – lead to what I call “awareness, concern, action.” When you become aware, then you begin to have compassion and feel concern, and out of that you take action.

————-

Sermon

When my oldest child, Martin, was younger, people would ask me about his hobbies and passions. My answer was always: he’s all about Stories. Whether it’s reading stories, writing stories, watching plays, acting in plays, or playing video games with great story arcs – he’s all about story in all its forms.

Over time, it dawned on me that I am also “all about story”. I love reading books, watching movies, watching plays, having long conversations where people tell me their stories, listening to podcasts of stories, and so on.

Professionally, on the surface, I’m not a storyteller. Not a novelist, or a playwright, or an actress…

I teach health education, childbirth classes, and parenting classes. I write non-fiction books about pregnancy, birth, and babies. I write blogs about parenting, and hands-on science experiments for kids. It’s all very practical, non-fiction kind of work.

When I teach or write, I’m great at logical structure and flow, I can easily come up with clear descriptions and clarifying examples, I quote statistics off the top of my head, and cite the relevant research. That’s speaking to the rational mind, the language Hecht calls Logos

But, the most powerful moments of my classes are when I tell stories – what Hecht calls Mythos. Now I don’t mean long, rambling stories. (Right? There’s nothing worse than being trapped by someone who is telling a long, irrelevant story and you just know that there’s never going to be a point to it…. ) No, the stories I tell are as short and tight as I can make them, telling just enough individual detail to make the story “real” – but always remembering what my goal is in telling it. An intriguing aspect of stories is that the better you tell the unique and intimate detail of one individual story, the more purely you can capture a universal experience.

So, I know that stories work. When I saw that our worship theme this month was Story, I saw a great opportunity to look more closely at how and why stories work to change hearts and minds. I found three key points I want to address:

- Stories Inspire: Story has a unique power to connect, getting past our rational mind and to our understanding heart.

- Stories Teach: Because stories connect, they are great teaching tools. Think of Jesus’ parables, Aesop’s Fables, the Taoist tales of Chuang Tzu, and the stories of the mullah Nasreddin… all help the listener to remember key lessons of their culture

- Stories Change Hearts and Minds. If you want to create change, one of the most effective ways is to tell a story that helps your listener empathize and understand what they have in common with those who want that change.

Another way to summarize this, offered by Kelli McLoud, a cultural diversity trainer, is that stories “connect [the listener’s] hearts to their heads, and that leads to work with their hands.”

Let’s look first at Inspire. Inspire is defined by Oxford Dictionaries as “to fill someone with the urge or ability to do or feel something.” Another definition of inspire is “to breathe in.” I believe that story helps us to breathe in the truth, which then fills us with the ability to do or feel something.

Earlier, in centering words, I shared the story of naked truth, and how being clothed in story helped her to open the villagers’ hearts and minds to welcome truth in. We’ve known that since at least the 11th century.

But modern neuroscience tells us more about why this is true.

We’ll start in that bottom right corner with cortex activity: Brain research has found that when someone just says facts and words, it only activates the two portions of the listener’s brain that process language. But when someone tells a story with sensory details and actions, it activates other areas of the brain. If the story talks about a smell, like perfume or coffee, the olfactory regions light up. Hearing sentences like “Paul kicked the ball” cause activity in the parts of the brain that coordinate movement.

Annie Murphy Paul in a New York Times article “Your Brain on Fiction” said “The brain does not make much of a distinction between reading about an experience and encountering it in real life; in each case, the same neurological regions are stimulated. … reading [or hearing a story] produces a vivid simulation of reality.”

Next, we’ll look at Mirroring, there in the bottom left corner… If you look at the brains of multiple people listening to the same story, the same portions of their brain light up at the same time. And their brain activity matches that of the story-teller. When we listen to the same story together, like here at church each week, this puts us all on the same wave-length.

Neural coupling is something that happens in conversation… if the two people are not communicating well, their brain activity is out of synch. When they start connecting and understanding each other, their brain activity matches up, although the listener lags behind by about 1 – 3 seconds as they process what they are hearing. When the speaker is telling a good story, the listener can catch up – sometimes their brain activity even anticipates what’s to come, responding to where the story is going. (There’s a CBC radio show called Vinyl Café, where the host tells fabulous stories… sometimes the audience can feel where the story is heading, and has this buzz of “oh, you know what’s about to happen?!” Stuart will stop and say “Now y’all are getting ahead of me. Wait for it!”)

So, Mirroring and Neural Coupling help us to connect emotionally with the story-teller and with other listeners, bringing us all into the same mind-space together.

A final thing that happens in the brain is the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter which helps us regulate our emotions, but also helps us set goals and achieve them. When a story stirs our emotions, we remember it better, because we’re designed to remember emotionally charged events. It’s even better when we hear the story in an environment where we feel safe and loved – that causes the hormone oxytocin to flow, which increases neuroplasticity – it helps our brains be more flexible and more open to learning.

So, when we take Naked Truth (or Logos) and clothe it in Story (or Mythos), our brains experience the sensory moments and the movements in the story as if we were actually sensing and doing those things. Our brains help us to feel connected to and similar to the people around us. And the emotions of the stories engage us, making us feel the emotions those around us are feeling.

All this combines into the power of story to Inspire Us… to help us to breathe in the truth, which then fills us with the urge or ability to do or feel something.

——-

The second key point about the power of stories is that Stories Teach. They teach in ways that we can understand, remember, and apply to our lives.

I want you to think back on some stories you may have heard over your life… stories that I know you remember…

If I say “slow and steady wins the race”, what story goes with that? [Tortoise and the Hare – Aesop’s fables – ancient Greece, about 600 BC]

If a princess kisses a frog, what happens? [He turns into a prince. Grimm’s fairy tales, 1830’s]

If a pig wants to build a house, what material should it use? [Bricks. Printed in 1840’s]

Who finds the genie in the lamp? [Aladdin] That story appears in the tales of 1001 Arabian Nights. Who’s the harem girl that tells stories for 1001 Nights? [Scheherazade]

Stories stick with you, right?

——

Many spiritual traditions include parables that teach how a good person behaves within that spiritual tradition. Think of Jesus’ parables of the Good Samaritan, the Prodigal Son, the Lost Sheep, the Mustard Seed.

Before written language, parables survived for generations of oral tradition because stories are so memorable. Even after written language, lots of classic tales continue to be told to generation after generation.

And we create new stories every day. We share them for many reasons, one of which is to teach. Again, stories help people to understand, remember, and apply what the teacher is hoping they’ll learn.

Jennifer Aaker, a professor at Stanford tells of a colleague who asked students to make a 1-minute sales pitch. They all used statistics – 2.5 on average. But only one out of ten students actually used a story in their pitch. The researcher then asked the class to write down everything they remembered about each pitch. Five percent of the students cited a statistic they had heard while 63 percent remembered the story.

A good teacher will still include plenty of facts and statistics that verify the validity of what they are teaching – that speak the language of Logos, but we weave stories in and amongst those facts to help them to stick.

I’m going to share with you an example of a story I tell in a childbirth class…. One of the messages I have for the dads, and other loved ones who will be supporting someone in labor, is that they need to provide the kind of support that works for the laboring mom, even if that looks very different from what they think they would find supportive in a similar situation.

I could lecture on this for several minutes, and my students would understand me, but they wouldn’t remember. I could give specific examples – that helps them to remember… but it doesn’t help them apply it, because they’re still listening just with their academic heads. But if I tell them a story with sensory details and movement and emotional content, they hear it with their hearts and their bodies, and they understand it, remember it, and can apply it.

So, I’ll share a story I tell from when I worked as a doula. A doula is a trained professional who provides emotional and physical support for women in labor.

Once, I was called in as a backup doula – the person who was supposed to attend a birth had a medical emergency. So, I walked into the labor room, truly knowing nothing about the laboring mom other than her name. I learned she was from Pakistan. According to every cultural expectation she had, her mother was supposed to be at her birth. Her mother could not get to the U.S. due to a travel visa issue. The laboring mom had several relatives in town, including her husband. But they were all male. Again, by every cultural expectation she had, men do not belong at a birth. So, the only person there to support her was me – a stranger, who knew nothing of her culture.

I asked her: If your mother were here, what would she do for you? I asked … “When you were young, and you were sick, what did you mother do?” She said “Oh, she would sit next to my bed, and stroke my hair and gaze into my eyes, and say “No one should ever have to suffer like this. My poor, poor baby.” [Pause]

Now, you have to understand just how different that is from my experience. I grew up in Wyoming, in a military family. We’re tough, independent folks. Dad’s theory was ‘If you’re not dying, just get up and go to school.” So this woman’s story of what her mother did just struck me as odd, and I kind of dismissed it.

So, her labor progressed. I did all the things I do when supporting a woman in labor, we walked the hallways, I rubbed her back, she took a bath. I was doing all my usual stuff and it wasn’t working. She kept saying “I can’t bear it. I can’t bear it.” I put on my Wyoming cheerleader hat, and was doing the “you’re doing great, keep it up” routine. And I could see it wasn’t working. Then I remembered what she had said about what her mother would do when she was sick. The next time she looked at me and said “I can’t bear it”, I said “I know. I’m so sorry. No one should ever have to suffer like this.” She looked at me and sighed “Yes….” Because finally I understood.

She went through the rest of labor, no longer suffering because she had the kind of support she needed. She gave birth to a beautiful boy with a headful of dark curly hair, whose crying settled the moment he heard his mother’s voice.

At this birth, I re-learned what I should have already known. Whenever you are supporting someone in distress, whether it’s labor, fear about a medical test, grief over the loss of a loved one, or whatever, you have to put aside your own assumptions about what would help you if you were in distress. You have to be open to them and their needs and their story. You have to be present and ask them what they need – and believe them when they tell you what they need.

So… that is how I use story in my work. Within that same class, I’ve quoted statistics. I’ve cited research. I’ve explained about the physiology of birth. I have spent much of class talking to their rational mind in the language of Logos. But the places that connect most deeply in helping them to understand, remember, and apply what they’ve learned, is when I step into this world of Mythos – the language of story.

—–

A final key point about story is its ability to change hearts and minds.

Andy Goodman, a consultant on non-profit communications, says “Facts alone don’t have the power to change someone’s story. If you’re in the business of changing how people think, what they believe, … how they act, you’re in the business of changing the stories in their brains. Stories are like the software of the brain. They tell our brains what facts to let in, and what facts to reject.”

Yes, the 11th century metaphor was that stories tell us who to invite to join us at our fire, and the modern metaphor is stories as the software of the brain… but both acknowledge the importance of stories.

In the book The Dragonfly Effect, Jennifer Aaker tells the story of Sameer Bhatia, a young Silicon Valley entrepreneur and Vinay Shakravarthi, a young doctor, who both had leukemia, and urgently needed a bone marrow transplant. Only 1% of the people in the bone marrow registry were south Asians. Their chance of a match was 1 in 20,000. Sameer’s tech savvy friends tuned to social media. They needed to share a story that would engage and inspire. So, they told the story of Sameer and Vinay – “brothers, husbands, sons…. Jokers, peeps… kind of like you (or your brother)”. And they included the story of how easy it is to organize a bone marrow registry drive, how easy it is to be tested, and how painless it is to donate if you’re found to be a match. “You could be a hero. You could save lives.”

They told this story on Facebook and Twitter and YouTube and they asked everyone who saw it to share it with their friends. Within 11 weeks, 24,611 South Asians had signed up for the registry.

Sameer and Vinay had matches, and received bone marrow transplants.

But it was too late, and both died.

But in the year after this drive, 266 other South Asians were matched and received transplants, and many more in the years since then. This would never have happened without the work of Sameer and Vinay’s friends.

The story they told engaged people and made them take action.

—–

Now, it’s important to know that not all stories work. Those long rambling stories with no point – yeah, they don’t work! A story that is only about an individual with no tie to the universal does not work.

We have to tell a story so that the listener is engaged, they identify with the subject of the story) and they can imagine themselves taking an action. If the story just says “here’s how this person is different from you”, they might feel bad for them, but they’re not motivated to do anything. But if the story says “imagine yourself in this person’s shoes”, they are more likely to connect to their experience, and want to support them.

I’d like to share an Islamic parable:

A blind boy sat with a hat by his feet. He held up a sign which said: “I am blind, please help.” There were only a few coins in the hat.

A man was walking by. He dropped a few coins into the hat. He then took the sign, and wrote some words. He put the sign back so that everyone who walked by would see the new words.

Soon the hat began to fill up. A lot more people were giving money. That afternoon the man who had changed the sign came to see how things were. The boy recognized his footsteps and asked, “Were you the one who changed my sign? What did you write?”

The man said, “I only wrote the truth. I said what you said but in a different way.”

What he had written was: “Today is a beautiful day and I cannot see it.”

Both signs told people the boy was blind. But the second sign helped them to empathize with the boy and see the abundance in their own lives, which motivated them to give.

——-

Michael Margolis, a self-proclaimed Business Storyteller (i.e. marketer) says “The stories we tell literally make the world. If you want to change the world, you need to change your story. This truth applies both to individuals and institutions.”

If we want to create change, we need to tell stories about how the world could be.

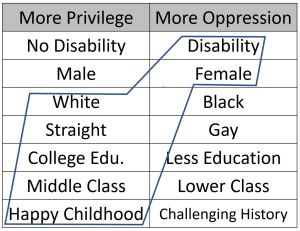

A few years back, I worked with Washington United for Marriage on the campaign for Referendum 74 for Marriage Equality. And although they certainly shared statistics and legal facts in their materials, an essential tenet of the campaign was that the real way to change people’s hearts and minds would be to tell stories. Stories of people who just wanted to get married.

It was easy for many people to buy into stereotypes about the gay and lesbian community, and think that they had nothing in common with “those people.” As long as they focused on the differences, they had no desire to support ref. 74.

But if they heard people who were like them tell stories about why marriage equality was important to them, and those stories were told in a way the listeners could relate to, the listeners were more likely to support referendum 74.

It helped if they saw ads, or spoke to phone canvassers, or listened to speakers at events. But, far more powerful than strangers telling stories, was if someone’s friends, family members, church members, or co-workers told them stories about why they supported marriage equality. So, Washington United asked their supporters to share their stories. That is the most powerful way to change hearts and minds. In the end, referendum 74 passed, 54 to 46% statewide.

Stories build bridges. They help us to connect with other people and empathize with their challenges. As poet Ben Okri said, “Stories can conquer fear, you know. They can make the heart bigger.”

I want each of you to think about a change you want to see in the world. Maybe it’s a big societal change – whether your cause is climate change, homelessness, gun violence, immigrant rights, LGBT rights, standardized testing in schools, or whatever. Maybe it’s just a small change in how you interact with someone in your own life.

I want you to think about the stories you tell yourself and tell others about this situation. Think about the stories that other people tell – the media, the people on the streets, your friends and co-workers. Where are we stuck in a negative story? If the story is “things are awful and they’ll never get better”, they won’t. If the story is “we’re all different and you just have to take care of the people who are like you,” that’s all we’ll do.

But if your story is “look at this other human being – see how they are like you and want what you want”, we are all more likely to care for each other. If you say “here’s my personal story and why I think things can get better and what steps I’m taking to make them better…” your listener is more likely to see what steps they could take to make their world a better place.

That is the power of story.

——————————————————–

Closing / Extinguish Chalice: Suzy Kassem in Rise Up and Salute the Sun, wrote:

“To really change the world, we have to help people change the way they see things. Global betterment is a mental process, not one that requires huge sums of money or a high level of authority. …If you want to see real change, stay persistent in educating humanity on how we are all more similar than we are different.

Don’t only strive to be the change you want to see in the world, but also help all those around you see the world through commonalities of the heart so that they would want to change with you. This is how humanity will evolve to become better. This is how you can change the world.”

Benediction: An Indian Proverb says: “Tell me a fact and I’ll learn. Tell me a truth and I’ll believe. But tell me a story and it will live in my heart forever.” Go forth, and tell your stories. Amen.