This is the text for a sermon I gave on March 12, 2017 at Northlake Unitarian Universalist Church in Kirkland, WA.

Identity

Our worship theme for March is identity. Many things shape our identity. Some of those influences are beyond our control – such as our race, our sex, the circumstances of our birth. But other parts of our identity are in our control… they’re based on the choices we make and the actions we take. Thus, we are shaped both by the circumstances which thrust themselves into our lives, and by how we choose to respond to those circumstances.

Identity is multi-layered. We have

- our internal identities – how we perceive ourselves.

- our broadcast identities – what we intentionally present to others – which may vary depending on who we are presenting to

- our external identities – how others perceive us, which is colored by their own life experiences and learned biases.

When human beings meet someone for the first time, we very quickly make assumptions about their identity. One study showed participants a photograph and asked for participants to describe that person. Let’s all try it… take a really quick look at a picture…

Now ask yourself – do you believe that person is trustworthy? Or not? Likeable? Or not? In the study, viewers formed remarkably consistent impressions after seeing an image for only 1/10th of a second.

Another study revealed that even if people were later given additional information that contradicted their first impression, it was difficult for them to over-ride their initial thoughts.

First impressions are snap judgments. When you meet someone for the first time, you do a quick tally of all the ways that person is either like you or not like you, is like the people you know and trust or is different from the people you know and trust. You take into account their race, gender presentation, clothing, hairstyle, weight, voice, accent and more. You create a story in your head, making a variety of unconscious assumptions based on what you see and hear, interpreted through your own lens.

When someone sees me for the first time, what most people notice is not my race, my gender, the fact that I wear glasses, the color of my shirt… the first thing they notice, even from a distance, is that I only have one leg.

And they begin constructing stories about me based on that singular fact. And yes, it’s an important fact, and the story has certainly helped to shape my identity. But my disability does not define me. There are many other things that form my full identity and that make me all that I am.

Today, I’m going to follow the approach of Ira Glass on This American Life, and I’m going to tell you a story in three acts. Act one: So, what happened to my leg? Act two: What is my identity? Act three: how does this relate to the broader questions of identity and privilege?

Act One – Why I have one leg

Let’s jump back to my ninth grade year. I was 15 years old. I’d had an easy uneventful childhood and early adolescence. I’d lived in the same house my whole life, and had a calm family life, with dinner on the table every night at 5:30 pm. My older siblings and my parents were always around if I needed them, but I’d been raised to be very independent. I was pretty athletic. I was happy socially, with plenty of friends. I was one of the top students in school. Overall, a pretty together, yet pretty typical kid.

Then… on New Year’s Eve, I found a lump on my right leg, just above the knee. I started freaking out, convinced it was cancer. In a panic, I went to my brother. He took a quick look, and declared with all the confidence of a 17 year old sage, “Eh, it’s just a swollen muscle. Wrap it with an Ace bandage and it’ll get better.”

So, that’s exactly what I did, for the next month.

Didn’t mention anything to my parents or anyone else, because it was just a swelled muscle… no biggie.

On a Sunday at the end of January, I went ice skating with my church youth group. By Monday night, I couldn’t walk without limping. When I showed my mom the lump, she scheduled a doctor appointment for Tuesday morning. I went to my doctor, who took one look, sent me for x-rays and sent me to meet with an orthopedist that afternoon. That doctor took one look at the x-ray, and told us he was sending us to Denver Children’s Hospital that night. The next two days were a whirlwind of tests, and a biopsy, and a diagnosis. Osteogenic sarcoma. Bone cancer. The lump I could see that was the size of my fist was half of a tumor which went more than halfway through my femur.

So, by the end of the week, there were decisions to be made. The best option was one month of chemo, then an amputation, then 8 more months of chemo. With that aggressive treatment, they estimated that my five year survival odds – the chance that I would reach 20 years old – was about 20%.

You would think that would have been terribly frightening. And it may have been for my family and friends. Though if it was, they hid that fear from me.

But, I didn’t hear the odds as an 80% chance I wouldn’t survive. I heard that I just had to be in the top 20% of people in this situation. And remember, I was kind of a cocky kid, confident in my own abilities. I’d never gotten less than a 90% on a test in my life… I was always in the top 10% of everything. So this was a piece of cake. If I just went through the required steps, it would all turn out fine. I never doubted that. (Gotta love an adolescent’s belief in her own immortality, eh?)

Thus began nine difficult months of chemotherapy, amputation, more chemo, physical therapy, more chemo, getting an artificial leg, more chemo… I was sick as a dog. I’d get my treatment, then spend 3 or 4 days vomiting… then I’d have ten days to recover, then start again. I was the same height I am now – 5’4” – and after a few months, I weighed 55 pounds. But I was back at school by partway through March, and finished 9th grade with my class. With an A- average.

I’d lost all my hair, and that was a big deal to me. I NEVER let anyone see me without my wig – even on my sick days at home. The idea of being bald was much more upsetting to me than having one leg. This ended up being a great coping mechanism in the long run – my hair would grow back and my leg never would…

A year after this process started, I was back in school full time, back to a reasonable weight, my hair was growing in, I’d gotten pretty good on my artificial leg, and I was learning to ski.

Five years later, not only had I hit that 5 year survival mark healthy and cancer free, I was in college in Boston and doing fine. I’d started as pre-med but moved into sociology. I’d decided I was more interested in supporting people through the social and emotional challenges of illness than through their medical care. I wasn’t skiing much, because the mountains of New England are disappointing when you’re used to the Colorado Rockies. But I’d started a new hobby of renaissance dance.

Ten years later, I was living in Redmond, married, working as a social worker at Children’s Hospital with kids with cancer and I was pregnant with my first child….

Now, it’s 35 years later. Today, March 12, happens to be the 35th anniversary of my amputation. Not only have I been cancer free all that time, I’m generally in overall better health than most of my peers.

So, that year I spent on chemo was, to be honest, a really crappy year. And, yes, my treatment resulted in me losing my leg. But, in retrospect, it’s not so bad when it buys you 35+ years of good health. It also bought me a whole lot of perspective. Having that close brush with death ingrained in me a few attitudes like “life’s too short to hate your job” and “anger and hate only waste precious life energy.”

When I was diagnosed with cancer, I was a 15 year old on the cusp of defining my identity and figuring out who I would be as an independent adult. So, losing my leg at that developmental point obviously had a big impact on shaping my identity. And yet… the fact that I’m a cancer survivor and an amputee is old news for me. There’s so many other things that matter to me at least as much. So, let’s move on to:

Act Two – What is my identity?

When we look at the question of identity, many times we’re asked to simplify things down to one label, like checking boxes on a form. The problem is those labels are defined through the lens of our dominant culture which makes a whole lot of assumptions in what options they offer. Choosing which box to mark isn’t always as straightforward as it seems.

The question “What is your gender” is almost always followed by two boxes.

The answer is not that simple, as my transgender son can tell you.

Race is not simple… a Chinese American man shared on an NPR story how picking just one box meant choosing one race over another – denying part of his ancestry. And choosing “other” wasn’t very satisfying.

And how about religion? There’s several of you I see here at church every Sunday… but I’m guessing many of you are stymied when asked whether you believe in a supreme being. I imagine most Unitarians want to write in “it’s complicated.”

So, when I see a form asking if I’m disabled, I have an internal debate about my answer. First, it’s the word… Although most advocates recommend using the word disability, I personally don’t like the word disabled, because it implies that I am not able to do things. I can do almost everything… I can ski, or ice skate, or roller blade… I can carry a kid. I can move furniture. So… I can’t run. And I can’t do ballroom dance or tap dance with complicated footwork like “step-ball-change”. But I don’t feel “disabled.”

I generally describe myself by saying “I have one leg” or “I use crutches.” If I had to choose a label, I like handicapped – because in sports, you give a “handicap” to the really talented person so other folks have a chance of keeping up.

But, beyond language choice, when deciding whether to mark a box, I end up asking “why are they asking the question?” (My husband and my kids are “Hispanic” and they ask themselves these same questions…)

- If it’s a demographic survey to assess needs (like “do we need to offer services for the disabled?”) then I always add my check mark to the tally to increase the chance that people who need services will receive them.

- If it’s something asking specifically if I need services, like a tour asking whether I would “need special accommodations”, I say no, because I don’t.

- If I think saying yes will benefit me at the detriment of someone else, I say no. For example, I was offered a scholarship for grad school that was earmarked for a person with a disability. I asked them to offer it to someone else. I could afford the tuition, and many could not.

So on paper or online, I can make choices about whether to reveal my disability. In person, in how I present myself to the world, I also make choices.

I could wear an artificial leg. I did most of the time back in high school and college. It made people more comfortable. Even if they knew it was an artificial leg, it was somehow easier for them to pretend that I was “normal.” But my artificial leg was uncomfortable to wear. It slowed me down. So, I stopped wearing it. It is more important to me to be able to move easily than it is to worry about how I look to others.

Yes, modern artificial legs are better. Maybe someday I’ll wear one. But for now, I don’t want one. It’s partially about mobility and convenience. But it’s also about identity. Wearing a prosthesis feels like trying to hide who I am.

Having one leg makes it hard for me to be invisible. People remember me. I often have strangers say things like “Hey, your kid just started school at my daughter’s school.” There were 100 other new kindergarteners this year, but I’m guessing other parents are less likely to be recognized at PCC, just two days into the school year.

Because my handicap is so visible, whenever I move through the world, I am representing “disabled people.” Many minorities experience this when interacting with a majority culture… the one woman in a tech company… the one person of color in an otherwise all-white workplace.

I am often asked to answer questions, or speak, or write on how to better serve people with disabilities. And I do, but I’m always very careful to say that I can only speak to my own experience, and other people with disabilities could have very different perspectives, based on their disability, how long they’ve had to adjust to it, their emotional reaction to that disability, and other parts of their identity – race, orientation, and so on.

My nature is to be extremely independent, and not ask anyone for help. Remember, I was raised in Wyoming, by a military family – we’re tough stock.

So I have to figure out when to ask for help, and also when to accept help.

Whenever anyone offers to open a door for me or gives me a seat on the bus, I say yes and thank you. I don’t need this, but I want them to have a positive experience, because the next time they see a person with a disability, I want them to offer their assistance. When I was pregnant and one-legged, on the rare occasion someone didn’t offer me a seat, I would give just a little look of surprise. Just enough to imply… “huh, I’m surprised you didn’t offer your seat. Good people look out for others, and it seemed like you were a good person…” They would then often look a little startled, realize that I was right, and give me their seat. In this case, I was using a little of my privilege as a white disabled woman to remind them that when any person comes on a bus that needs the seat more than they do, they should stand up.

When I pull my car into a parking lot, I decide whether to use the handicap spaces. Years ago, I avoided them, because I don’t need them. I can walk for miles. But disability rights advocates encouraged me to rethink that. If every time people pull into a parking lot they see lots of empty handicapped spaces, they are tempted to use them. If instead, they see me getting out of my car on one leg and crutches, they think “wow, it’s a good thing no one took that space.” So, I never take the last handicap space, because I am certain someone will come along who needs it more than me. But if there are several spaces, I always take one.

So, even after 35 years as an amputee, I’m still sorting through identity questions about whether I view myself as disabled.

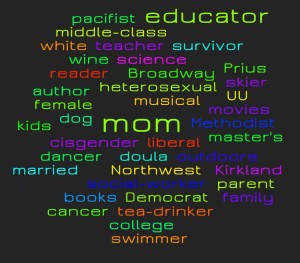

But really, most of the time, when I think about my identity, I don’t focus on just one label because so many others apply. There are so many things that make me me.

In the video we watched at the start of the service (see below), all the participants were put into a box based on one identity. All they could see was what made them different from other boxes. But then, as the host listed other identities, people began stepping forward, and seeing all the things they have in common.

What makes me different from you is that I only have one leg – that’s the first box people put me into. But there are many other things that define me.

I may have some of these in common with many of you – think about when you would step out of your box and join me…. I am a cancer survivor. I am a heterosexual, cisgender woman. I’m married and have been married to one man for more than half my life. I am a pacifist and a bleeding heart far left liberal. I’m a skier, a swimmer, and a dancer, and I love long walks. I am a movie buff, a musical theatre fan who sings Broadway show tunes in the shower and an avid reader. I grew up Methodist, and now I’m UU. I am a social worker, a doula, a health educator, a parent educator, a kids’ science teacher, and an author. I live in Kirkland, and am a Pacific Northwest person. I start every day with a cup of tea and enjoy a glass of wine with dinner. And probably the most important identity to me is that I am a mom. Parenting my three kids is the most important thing I do and the one that I try the hardest to get right.

And that identity has led me to my current career. I work as a parent educator for Bellevue College. I teach parents about everything related to parenting, from potty training to early literacy to emotional development.

Why do I think it is so important to get parenting right in those early years?

Last week, in his sermon, Mike Lisagor shared a snippet from his childhood: “We moved several times. My dad was always losing his job or losing his temper. My oldest sister was always running away from home.” Mike talked about how fear and despair shaped much of his early life, and how hard a path it was for him to find his way back to hope.

I had the opposite experience. I had a childhood that taught me that the world was a safe place filled with good people. I grew up trusting that things would always turn out OK in the end. So cancer at 15 didn’t scare me, because I had the privilege of a happy childhood.

The author of the book, Secrets of Happy Families, Mike Feiler says “When faced with a challenge, happy families, like happy people, just add a new chapter to their life story that shows them overcoming the hardship.” That was certainly my experience. My goal with the families I work with is to help them build that same resilience. I want children to hear messages like we heard in our Time for All Ages story, when Molly Lou Melon heard from her grandma: “Believe in yourself and the world will believe in you too.”

Feiler also recommends that we tell our children about our challenges and how we’ve overcome them. He says “if you want a happier family, create, refine and retell the story of your family’s … ability to bounce back from the difficult ones. That act alone may increase the odds that your family will thrive for many generations to come.”

It’s time for…

Act Three – How does my experience relate to the broader questions of identity, privilege and intersectionality?

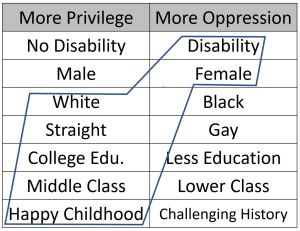

As I said at the beginning, many things shape our identity. Some are based on the choices we make and the actions we take. But some influences are beyond our control. Yes, for me that included a childhood cancer, but for all of us, that includes our race, our biological sex, etc…. And that’s why we need to talk about privilege and intersectionality. Let’s quickly define terms:

So, what is privilege? If we acknowledge, as we must, that on average, African Americans as a group experience more discrimination or oppression than Caucasian Americans, that also says that white people have privilege compared to black people. Privilege is the opposite of oppression. So, let’s look at a few categories: This is how most people would fill in this chart of what groups in America are more likely to experience privilege.

What is intersectionality? We all have multiple identities, and are all members of more than one community at the same time. When we add these all together, they compound. For example, a black lesbian experiences racism and sexism and homophobia.

She has fewer opportunities and faces more challenges than a white lesbian or a straight black man or a gay white man.

I can honestly say that my disability has not been a big obstacle for me. But I have to acknowledge that much of that is due to privilege…. When most of the other cards in the deck are stacked in my favor, it’s easier to ignore the disability card.

For example, 40% of people with disabilities report experiencing discrimination in the workplace. My disability has never limited my ability to get, do, or keep a job. It helps that I’m well educated – I have the privilege of an educated family that helped me do well in school so I went to college on a full ride scholarship, and then I went on to grad school because my husband’s income could support our family. But part of my job success is also because I am white, straight and cisgender. And I’ve chosen female dominated fields, so my gender has never been an issue.

I have been, overall, blessed to live an easy life. I mean, sure, I had cancer when I was 15 and lost my leg… but on balance, my life is pretty darn good… And I do consciously think about the ways I can use my privilege to speak out and support those who do not have the same privileges, and to raise awareness of these issues.

So, I have shared today my story of living life on one leg. But another amputee’s story – their identity – might be very different.

For all of us, our identities – the unique lights we let shine – are products of all our history, our group identities, accidental encounters, beliefs, choices and actions. We reach our fullest potential when we can embrace all the parts of our identities, and not limit ourselves to someone else’s story about who we are. Our closing words are from Spirit Daily:

People label us. They put a tag on us. And too often, it sticks. We start to believe the way we’re perceived …[which is] based on assumptions, false first impressions or old information…. Joy comes with greatness – the greatness of motherhood, the greatness of being a great janitor, the greatness of a life lived for others. It is labels – and our accepting those labels – that prevent us from achieving bigger spiritual things. Go for the greatest “you.” Go for the best you can be – no matter what others around you think.

When we sing about “this little light of mine”, remember that all light is made up of many colors of light shining together. So let your own unique light shine… sharing all the contradictions that make you you. Let it shine, let it shine, let it shine.

Gosh, what a great essay. I am so grateful and appreciative that you share your perspective and skills with us, so we all can grow. Thank you.

LikeLike